I began to be intrigued by the idea of Celtic chariots when I expanded one of my “Dawn of Ireland” characters, Owen Sweeney. Owen actually began as a mysterious, villainous man in a book that preceded my Dawn of Ireland novels. His past and his personality are slowly revealed throughout five books (so far).

Quite without my willing it to happen, a man in a wheelchair began to take on immense proportions. Always described as “bigger than life” for his towering intellect and personality, Owen Sweeney MacNeill is actually half a man. He has spent the past twenty years confined to an invalid’s cart, his legs no more than withered sticks.

Owen had a tragic past—from the time he began his anguished search for a father he would never find, to the incident when his legs were crushed by a frightened horse, to the loss of his beloved wife and his near-death in a currach tossed into the sea—all this and more makes up the many-wefted tapestry that reveals the complex man.

In the novels Captive Heart and Fire & Silk, Owen needs a way to travel. Therefore I had to research the kind of “chariot”-like devices that could have been used in the fifth century AD.

First, I discovered that wheeled invalid carts have been around since the days of the ancient Greeks. This photo (L) of a sculpture shows a man possibly sitting in a wheeled conveyance. The photo below of the wooden wheeled chair is much later than my stories, but the construction is not so far from what could have been possible at the time. The most likely way Owen could get around in his own home would be similar to a small ox-cart. He turns the wheels by means of his massive arms, whose muscles have developed preternaturally from the strain of pushing himself from place to place.

Just as important as making his way through his own home, Owen must travel long distances to set up a new domain in the northern expanses of Ireland. After all, it is this man who gave his name to Ireland’s Inis-Owen and Tyrone (Tyr, or Land, of Owen). Luckily, his own nephew Michael MacCool is a gifted craftsman who has built a fleet of currachs and a gracefully-prowed longship.

Therefore I, in the guise of Michael, had to construct a chariot.

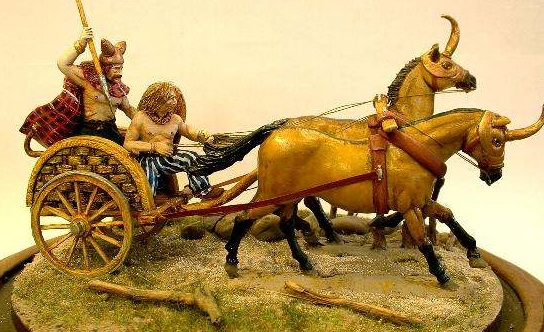

The first question one might ask is whether the ancient Celts even used chariots. The scholars agree that they did. In the Bronze-Age epic the Bo Tain Culaigne, war chariots are noted constantly. Reconstructionists have given us ideas of what those chariots must have looked like: double yoked, with a passenger “basket” made from pliable branches; spoked wheels; a kind of floating suspension so that the chariots could travel safely over the rugged landscape.

The Irish Gaelic word for “chariot” is carpat, itself a cognate of the Latin word carpentum, their word for “chariot.” The Gaelic word no doubt entered the language through the Romans, who did not much venture into ancient Ireland—or even Scotland—but who were past masters at the art of building and using chariots.

In Captive Heart, the narrator Caylith sees the finished chariot that Michael has just built:

Framed by strong oak, fashioned in the center with latticed wicker and strengthened in strategic places with forged steel, the chariot was about six feet wide, including the wheels, and it stood at least that high. From the center, like a tongue, there jutted a long, flexible pole attached to an axle. I knew the pole would be attached on each side to two horses, for it ended in a metal yoke.

The wheels were six spoked, the rims covered in wrought iron for added strength. I saw that the hubs were also metal.

I turned to Michael. “The wheels—so small—”

“Aye lass, this is me own invention. The bigger the wheel, the weaker the wheel. An’ the bigger it is, the heavier it is. So these are only about a foot or so high, an’ spoked for added lightness. The metal hubs give it strength. What do ye think?”

“Ah, is Owen supposed to sit with his—his legs down, or spread before him?”

“Two people sit side by side, Cay, as if they sat on a bench. Ye see here? Their feet are protected by a board, an’ they can sit with support for their back. An when they are tired, the back can be laid flat. They can enter and leave by the rear also.”

“Two people sit side by side, Cay, as if they sat on a bench. Ye see here? Their feet are protected by a board, an’ they can sit with support for their back. An when they are tired, the back can be laid flat. They can enter and leave by the rear also.”

I saw that the carriage itself—the “basket” that held the passengers—was very lightweight, almost like the latticework of the clay-and-daub houses or the frames of Michael’s currachs. At the joints, the lattice was interlaced with strong steel rings. I ran my fingers along the latticework while Michael talked. “The best part of all is the way the platform hangs free of the wheels an’ the axle. If it hits a rut, the whole chariot does not jump an’ dislodge the riders. “

Yes, that really was the best part. I could see, from the point of view of an ignorant observer, that this chariot would cause Owen no pain as it jumped and quivered along the rough countryside. In fact, he could ride like a very king. He could hold the reins, or Moc could be the driver.

“Michael, it is—beautiful. I can think of no better word.”

“Go raibh maith agat. It tested me brain, an’ the next one shall be better.”

Here is a scene from Fire & Silk (to be re-released), where Owen and his stalwart sons are traveling from their home in Inishowen to the home of his brother in (present-day) Donegal:

A curious procession moved south, beyond Snow Mountain. It bore slightly west, away from the worst of the foothills in the high pastureland. In front rode a quiet redheaded man on a black stallion. He turned his head often to gaze at the woman next to him, one whose long, dark hair lifted like wings around her face.

He turned in the saddle to glance at his companions. Behind him, there rolled and rattled a vehicle borrowed from the poetry of the filí, bards of the kings. The man in the chariot was large and heavy browed, and he shouted out to a brace of strong horses as he guided the vehicle around a rocky outcropping or a small gully. Beside him sat a shapely little woman, her deeply black hair swept up with a large ivory bodkin, her eyes sometimes on the driver and sometimes gazing ahead.

Behind the chariot, three very large men sat astride horses, shouting and laughing, sometimes singing. And in the rear walked six packhorses. This was the caravan of Owen, King of Inishowen, who traveled to meet his own brother for the first time.

I hope you will read the Twilight of Magic and the Dawn of Ireland novels . . . if not for the love stories, then for the evolution of a complex man, the character known as Owen Sweeney MacNeill.

Erin’s fantasy series:

Erin’s Historical Romance:

Erin’s Contemporary historical MM Romance:

~The Iron Warrior http://amzn.to/2n3sTgh

Fascinating. I like the engineering details most of all.

LikeLike

Hi, Nya, and thanks. I love the engineering stuff too. The verbal description in the piece is from the mouth of 18-year-old Caylith, a professed non-scholar, who thinks of libraries as “parchment prisons.” So her description is vague and child-like. Thank God I didn’t have to describe it from the pov of someone who knows what the hell they’re talking about….

LikeLike

Research may be the funnest part of writing a story. I’ve learned tons from mine. 🙂

LikeLike

Hi, Fen. I agree. I’m a bibliophile anyway…This entire 30-some-article blogsite is based on only a small part of the research I did while writing the Dawn of Ireland books. Good to “see” you, my friend. I’ll catch up with you on your site soon. 😀

LikeLike

FASCINATING stuff… I love where your stories take everyone, Erin. This sort of stuff is wonderful.

LikeLike

Oh, I became so immersed in the 433AD time of St. Patrick that you could have put a léine on me and wouldn’t know me from a native…including learning a hefty amount of Gaelic phonology and a bit of an Irish Gaelic vocabulary. Here’s the funny part about the Owen character: he was invented in a book that preceded the Romannce novels, and I had him thrown into the north sea, tied in a currach, fully intending for him to perish. Boy, was I wrong. He came bobbing to the surface in the next book and hasn’t yet left.

Thanks, M, for your visit and your warm words.

LikeLike

I never would have thought about the floating suspension – which, of course, would make a huge difference in the ride for passengers. Amazing detail, I love things like this 😉

LikeLike

Hi, Sessha! Yes, I was also totally amazed at the ingenious minds of those early Irish warriors. It makes sense to us now, but it took several centuries for people to figure it out…would you believe, on the island of Éire. And then the technique was lost for several hundred more years after Patrick tamed those wild-ass Irishmen.

LikeLike

Interesting, Erin. I’ve done research on chariots but the Egyptian ones for construction in horse model set-ups. Research for historical pieces is so important and you sound like you take meticulous care at getting things “right” for the readers. As one, I appreciate those little things that make such a difference in a well-told story. Thanks for sharing the information.

LikeLike

Thanks, Cynthia. I appreciate your concern for the detail. Once I read a story about 3rd century Romans where the novelist had a Cinderella-type carriage rattling along Hadrian’s wall. Well, the Romans were very adept at making chariots–but an enclosed carriage was not to come for several hundred years in the future. The wrong history can almost ruin a good tale!

LikeLike

Don’t ya just love the spikes on Boudica’s chariot on the London statue of her and her daughters 🙂 Great info here. Thank you

LikeLike

Hi there, Judy. I’ve often wished I could spend more time in London. I haven’t seen the statue, but Id like to.

I sure welcome you to my blog, and I hope from time to time you’ll find an article to enjoy, and to comment on. Thanks for the visit. 🙂

LikeLike