While writing all the Dawn of Ireland books, I was drawn to the rich folklore of Éire, and throughout the novels I attempt to capture some of the music, the heroism, and above all the bawdy spirit of the original tales. Many followers of Gaelic lore know that “The Cattle Raid of Cooley” (Táin Bó Cúailnge) has been hailed as the Iliad of ancient Ireland. It is, in a nutshell, a saga of mighty battles fought over the ownership of a fine red bull.

Like Homer, the singer of the Cattle Raid, the Táin, was not one man but scores of men–poets, ollahmhs, filí--whatever we call the people who sang the great mead-hall ballads of warriors and maidens, gods and goddesses, those creative people with no name who spanned centuries.

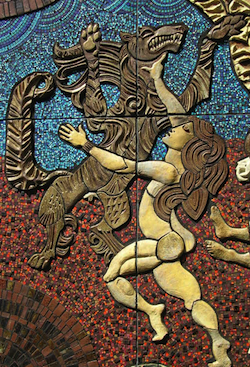

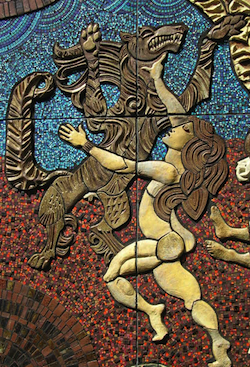

Of all the characters in the Táin, probably two stand out more than the others–the hero Cú Chulainn and the warrior queen Maeve (in Gaelic, Medbh). As an archetypal figure, Maeve is also associated with Queen Mab of England and even the Welsh Morgan La Fey, among many others. Today I want to talk a little about the Gaelic Maeve and to present to you an alternative version of the cattle raid–a bawdy story I wrote for The Wakening Fire that spoofs the original and yet, I hope, remains true to the spirit of the sexually unquenchable, powerful queen of Connacht.

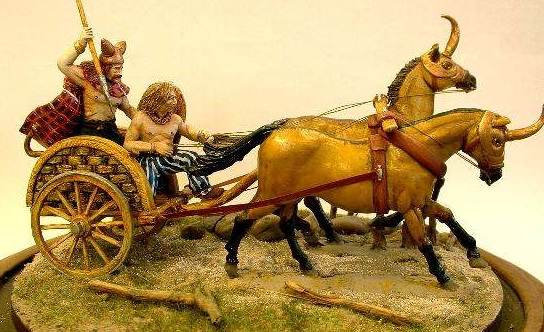

The infamous cattle raid of the original epic was indeed started by Maeve. Jealous that her husband Ailill had one more possession than she–a fine red bull being cared for by a neighboring noble–she sets the wheels in motion that result in years of warfare and bloodshed, including the deaths of her children.

The infamous cattle raid of the original epic was indeed started by Maeve. Jealous that her husband Ailill had one more possession than she–a fine red bull being cared for by a neighboring noble–she sets the wheels in motion that result in years of warfare and bloodshed, including the deaths of her children.

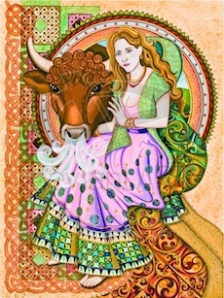

Many pictures of Maeve show her next to a red bull. The war began one night during a tender moment of pillow talk, when Maeve begins to feel the stirrings of possessiveness that result in the cattle raid. In my own story (possibly true to the original intent), her craving for the red bull is really a reflection of her renowned sexual appetite.

In the following excerpt from The Wakening Fire, Caylith’s erudite friend Brigid has a plan to arouse her husband. She tells the company sitting around the campfire the tongue-in-cheek female version of the famous Cattle Raid, making the red bull not a possession of her husband, but her own. In this version, Maeve is far more interested in the horn than in the bull….

In the following excerpt from The Wakening Fire, Caylith’s erudite friend Brigid has a plan to arouse her husband. She tells the company sitting around the campfire the tongue-in-cheek female version of the famous Cattle Raid, making the red bull not a possession of her husband, but her own. In this version, Maeve is far more interested in the horn than in the bull….

One night around the campfire, Caylith calls for a story:

“It is time for a tale,” I said to the company at large.

“Abair scéal,” said Brigid. “The ages-old cry for a story. What shall we hear tonight?” She settled back on the raised knees of Michael, her head thrown back and all her golden hair spilling over his legs.

“A tale of cattle,” I said.

“Then the teller must be me wife,” said Michael, stroking her soft curls. “Her namesake, the goddess Brigid, is the protector of cows.”

“Yes,” said Brother Jericho. “And tonight is her night, of all nights of the year. Um, to the local people, that is. Father Patrick is hoping to alter those old folk beliefs.”

She looked up dreamily to the top of the pines, where a few stars stood out against the black of the sky. “Tá go maith. I shall tell, for the many thousands of times over, the story of the great cattle raid. But from the point of view of a woman—the powerful queen Maeve.”

I knew the story, of course. It was one of the oldest in Éire, told by men as they quaffed their beer, recited by poets in the great mead halls of kings. For it was a tale of manly conquest, of warrior against warrior. The cattle raid itself was a mere excuse for a tale of bloody might versus might. I would enjoy a female version, and I settled back in the hollow of Liam’s shoulder to hear her story.

We all know that Maeve was a beauty [Brigid began], and she was the queen of all Connaught. Her fortunate husband, Ailill, enjoyed a life of sensual gratification because of her ready thighs; and a life of ease because of her bounty. And he knew it. She was loath to remind him, as long as he remained loving and true—and as long as he did not challenge her wealth.

One night, Maeve and Ailill were lying back on their golden bed strewn with mink furs and nosegays of lavender, basking in the glow of their lovemaking.

“Darling,” said Maeve, “the size of your loins is as great as that of my strong, red- eared bull.”

“Really?” he murmured. “I would see this bull. For I say my great shaft is more like that of my own white-horned bull.”

“Challenge me not on this point, dear husband. How are you qualified to judge the nether horn of a bull?”

Ailill was rankled at her teasing. “Because I am a man,” he said. “Because White Horn belongs to me, and his size is a matter of pride.”

“Say you that your possessions—even a single bull—are greater than my own? Say you that my Red Ears cannot measure his horn against that of your White Horn?”

“Yes,” he said, convinced of his own manly prowess, blind to his wife’s growing vexation. For he was beginning to feel again the stirrings of desire, and his words amounted to an invitation to prove his proportions were worthy.

Now Maeve was no fool. She knew exactly what Ailill was doing and she, too, craved his nether horn for the second time that night. But she was also very competitive. She thought she would have his bull, and her own, too, thereby increasing her wealth and enjoying his dimensions at the same time.

“I propose a raid,” she said with a fire in her eye. “If you capture my red bull, I will give you the debate, and you may use that bull in any way you see fit. But if I capture yours, you must yield it to me any time, night or day, in any way I see fit.”

To unquenchable Maeve, this challenge was not just a competition—it was a way to ensure unheard-of gratification from her prodigious husband. But to Ailill, suddenly stubborn and proud, it was a way to best his overweening wife.

“By tomorrow night,” he said rashly, “your red-eared bull shall be mine.”

He turned his back then and slept, much to Maeve’s disgust. When he was snoring loudly, she crept from their fine bed and donned her leather slippers. Drawing her silken tunic around her ivory shoulders, she walked to the byres of Ailill where she knew a large white bull lay sleeping.

“O White Horn,” she murmured. “I have come to take you to my prize heifer, she of the lovely red shoulders, she who has never known the nether horn of a fine young bull.”

He opened one eye, loath to rise from the shelter of the byre and the plenty of the hay haggard.

“And,” said Maeve, “to sweeten the feast, my second virgin heifer waits for you, she of the deep black coat and milk-white chest.”

At these words, White Horn heaved himself to his hooves and began to beat his shaft against the sides of the byre in anticipation.

“Follow me,” she said sweetly, and he did. For Maeve knew the weakness of every male—and that is the promise of yielding thighs with no payment on the morrow.

As soon as White Horn entered her own byres, she shut the paddock firmly and called her strongest guards to stand sentry. “So that none may disturb you,” she told him with a broad wink.

And then she returned to her mink-soft bed to exact her payment.

Brigid stopped speaking, and she and I started to laugh—first softly, then louder, until I felt tears at the corners of my eyes. “Brigid, you are a poet. If you were not a woman you would stand by the shoulder of the high king himself as his ollamh.”

“Ah, I think the woman’s perspective may rankle even the most benign of kings,” she said, raising her eyes to look at her husband.

Michael looked as if his dinner were not quite settled in his stomach. “The next tale at this fire, young Brigid, will be told by Ailill.” He seized her shimmering hair and pulled her head toward his, and I could see that her story had aroused him deeply.

The chapter ends with Caylith and Liam’s own reaction to the story, but I leave it right here for you to imagine.

The Wakening Fire is now available on Amazon: http://goo.gl/XRYvA

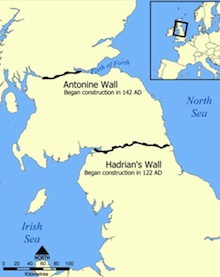

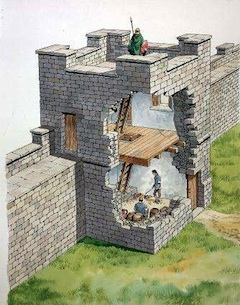

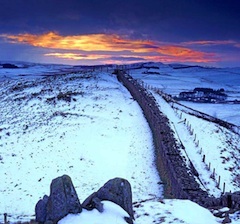

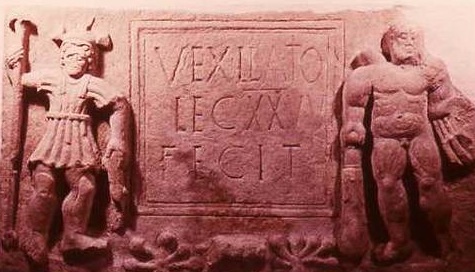

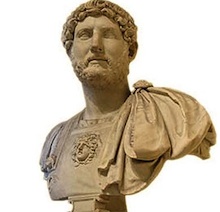

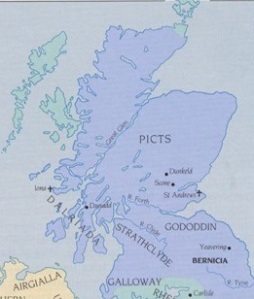

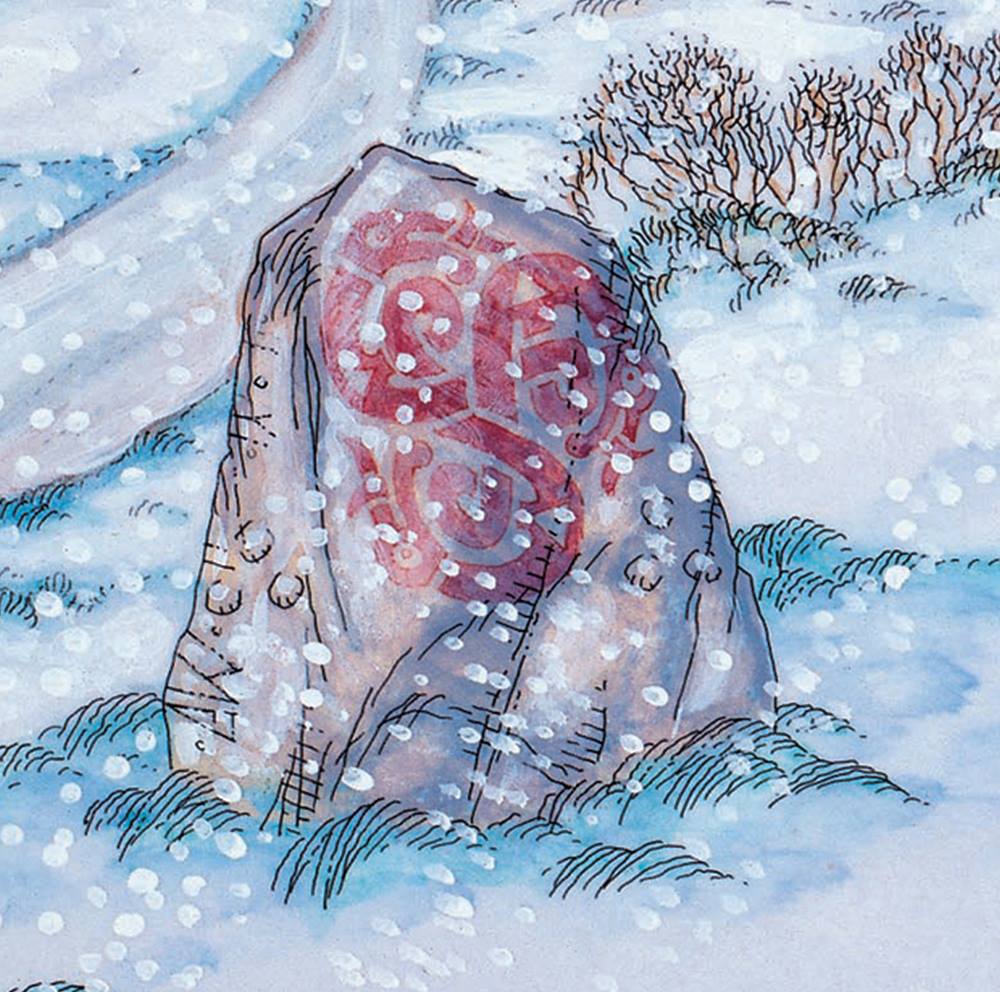

I am fascinated by the Wall of Hadrian, and I have placed two of my characters in, on, or around that wall. Gristle, known as Marcus when he was a soldier, was stationed in the nearby hills of the Lake District in Warrior, Ride Hard. He and his soldiers were pitted against the roaming Pictish tribes. In the sequel titled Warrior, Stand Tall, I introduce a character named Dub or Dubthach who fought at the wall and ventured beyond to marry a Caledonian maiden.

I am fascinated by the Wall of Hadrian, and I have placed two of my characters in, on, or around that wall. Gristle, known as Marcus when he was a soldier, was stationed in the nearby hills of the Lake District in Warrior, Ride Hard. He and his soldiers were pitted against the roaming Pictish tribes. In the sequel titled Warrior, Stand Tall, I introduce a character named Dub or Dubthach who fought at the wall and ventured beyond to marry a Caledonian maiden.

To slice a big sun at evening–

To slice a big sun at evening–

Of course, I bade her dismount, and I poured a cup of water from a jug and proffered it to her. She drank willingly, and she thanked me kindly. “For whom do you draw water?” she asked me.

Of course, I bade her dismount, and I poured a cup of water from a jug and proffered it to her. She drank willingly, and she thanked me kindly. “For whom do you draw water?” she asked me.

My son rebelled against the priests’ attempts to convert him. Even from an early age, Owen was headstrong. He told me often that there could be no blessed heavenly father, for he himself had no father. What kind of heavenly father would take away a child’s father before he could know him? I blame myself for his unbelief. Surely I alone kept him from knowing the comfort of our Lord.

My son rebelled against the priests’ attempts to convert him. Even from an early age, Owen was headstrong. He told me often that there could be no blessed heavenly father, for he himself had no father. What kind of heavenly father would take away a child’s father before he could know him? I blame myself for his unbelief. Surely I alone kept him from knowing the comfort of our Lord.

One day, I was walking through a glen with my wolfhounds, playing and laughing, when a file of horsemen broke through the far line of trees. I could see at once that they were men of high birth, for the bridles of their horses were silver and the robes of the riders were trimmed in sable.

One day, I was walking through a glen with my wolfhounds, playing and laughing, when a file of horsemen broke through the far line of trees. I could see at once that they were men of high birth, for the bridles of their horses were silver and the robes of the riders were trimmed in sable. “But your first wife Rídach is still alive,” one of them reminded him.

“But your first wife Rídach is still alive,” one of them reminded him. Day after day, Cloud lay with me, and we loved each other more every day. One day, I found that I was heavy with his child. When I told my lover, he was filled with dread. “O Nuala, I fear for the safety of our child,” he cried to me. “For Rídach will suffer no child, except from her belly, to call himself my own. I fear she will set her own mother on you, a woman of cunning and wicked ways.”

Day after day, Cloud lay with me, and we loved each other more every day. One day, I found that I was heavy with his child. When I told my lover, he was filled with dread. “O Nuala, I fear for the safety of our child,” he cried to me. “For Rídach will suffer no child, except from her belly, to call himself my own. I fear she will set her own mother on you, a woman of cunning and wicked ways.”

In this historical romance series called “The Dawn of Ireland,” the reader will find myths and short tales, poetry, songs—and a story that weaves through all of them. It’s the saga of a man named Owen Sweeney. In the next several blogs,you’ll read a fantasy tale called “Nuala’s Secret” excerpted from the novel Wakening Fire.

In this historical romance series called “The Dawn of Ireland,” the reader will find myths and short tales, poetry, songs—and a story that weaves through all of them. It’s the saga of a man named Owen Sweeney. In the next several blogs,you’ll read a fantasy tale called “Nuala’s Secret” excerpted from the novel Wakening Fire.